unabridged version

Whether we realize it or not, making illiteracy a thing of the past will require far more than big speeches and grand declarations about the importance of knowing how to read. It will take work. The question is: are we ready to do what is necessary?

In August of this year, I created a project called “Labour of Love” in Kingston and Montego Bay. Part street performance and part activism, I wanted to see what would happen if love – not charity, shame, punishment, guilt, obligation – was the driving force for engaging in intentional, and hopefully, transformative social action in Jamaica’s public spaces. In ten days, I did a variety of activities: made sidewalk art, crafted wills, distributed reading material, gave away vegetable seeds, and did bra fittings. And for half of that time, I worked with school-aged children on the sidewalks of downtown Kingston. Armed with rubberstamps, crayons, pencils, markers, word and math games, and a plethora of worksheets, I tried to tailor each child’s activities to their abilities and interests. Age was not a useful predictor of any ability, as I discovered. A ‘class’ of 5 children quickly grew to a ‘school’ of over 20 children by the end of the week.

“School” as the children called our meetings, lasted from late morning or early afternoon until just before nightfall. The sessions were unstructured, driven primarily by what the children wanted to explore. Beginning with a reading activity – using children’s classics like Are You My Mother? By P.D. Eastman or the enormously popular I Spy Book of Picture Riddles – we would discuss the children’s responses to the material, and then moved on to another activity informed by the discussion. Reading about a baby bird who went in search of its mother led me to ask the children to select three characters from the rubberstamps, and to create their own stories based on the relationship between the characters. They created an art gallery by putting their pictures on the wall, and took turns telling their stories to each other. Children passing by listened in and even chose to participate as well. Not even the background noise of police converging on the area to remove vendors was enough to distract them. We typically ended with Word Bingo, where everyone had the chance to win pencils, sharpeners, and erasers. Punctuated by the children’s declarations of who was “sweating”, i.e. on the verge of winning that round, the games went on until I was exhausted; they never seemed to get enough of it. The older children took on more active roles, such as volunteering to call the words, keeping track of the game, and gathering and distributing the supplies as needed. I rewarded them with pencils for being helpers.

In those five days, these children were just like every other child in every other place. When they found something that they enjoyed, they wanted more and more of it. At the end of the day, the disappointment on their faces only evaporated when I answered “yes” to the question of “Yuh comin’ back tomorrow, miss? Seh yes!”

Our final session was held in Tastee Patties, one of several patty shops in the area which function as ad hoc daycare centers for the children of sidewalk vendors. The patience and generosity of the store manager was outstanding. He chose not to tell me that the store had closed until over an hour later; he said he really didn’t want to disturb us. Just before I left, I prepared a packet of materials for one of the employees; she would never have let me out the door otherwise.

The response of the public was overwhelmingly positive. One woman tapped me on the shoulder to get my full attention. She said that she felt compelled to cross the road and come to speak with me after having stood and watched, in admiration, how focused the children were and how much fun they seemed to be having, in the middle of all this, as she gestured to the hubbub of commercial activities around us. Parents inquired about the cost of participating, how often the class met, whether I was a teacher, and if I was taking any new students. Sometimes they left their children with the group, or went to fetch the children so they could participate. One parent was rather forthright: why, she asked, hadn’t I been doing this all summer or planned to continue, given how much the children were enjoying themselves? I invited her to pick up where I left off.

Many persons made the experience possible for the children. The vendors were delighted at the children’s involvement in a learning activity, helped find seating, and actively encouraged them to “pay attention” or even to return to “class” when some wandered off. One woman –a vendor and a parent – secured prime sidewalk space for us; others relieved their children of selling duties and sent them to participate; still others sent refreshments for me. Passers-by offered words of support, welcome, and approval, and the police didn’t try to relocate us. The children acted and felt like they were part of something special.

I also talked with many of the parents about their individual child’s needs. For me, it was important to affirm, and encourage their belief in their children’s abilities. They already understood the importance of their support and attentiveness to the children’s development; getting people to listen and to help them access the appropriate resources was the challenge they faced. As I packed up for the last time, one parent pulled me aside to tell me that she had decided to change her daughter’s diet, particularly to remove the sugary drinks, and encourage her to drink water and milk instead. Television was now out of the question, she added, because that took time away from reading. Neither of these issues had come up in earlier conversations. I just smiled and nodded. Sometimes I cried on my way home in the evenings, out of exhaustion and happiness. Although brief, I got a glimpse of what happens when one makes an effort to remove the material and ideological obstacles to literacy and replace them with love, no strings attached.

It is this recent experience that frames how I hear the concerns being expressed about the growing problem of illiteracy in Jamaica, especially among youth. It seems pertinent to ask: When was illiteracy not a social issue in Jamaica? This is not something new. If one believes that full – not partial – literacy of the population is the ultimate goal, then an 86 percent literacy rate was never good enough. Forget that such a figure, first estimated in 2006, varies up and down depending on who is calculating it. The most recent figure being cited is 80 percent literacy, which means 20 percent of all adults in Jamaica are illiterate. Also forget that the last actual survey of literacy in Jamaica was done in 1999. What we have is a profound problem in perspective: which side of the literacy equation do we choose to look at?

Since the late 1980s, successive Jamaican governments, along with nongovernmental and charity organizations, have chosen to accept that illiteracy in any part of the population did not constitute an urgent issue to be resolved, as long as the number seemed high enough. Apparently, they did not realize that a 14 (and now 20) percent illiteracy rate among adults (measured as 15 years and older) means that we have a whole lot more illiterate children. And those most of children will grow up to become illiterate adults, unless there is systematic intervention to address this. And that the same processes that created those illiterate children and adults are still hard at work. Social problems don’t usually dry up and blow away; they typically multiply in intensity and complexity. Ignoring them, and better yet, doing precious little to minimize them is not doing anybody a favor.

Still, as social problems go, illiteracy is a relatively simple one to fix. But the solutions proposed thus far, when they are not aiming to shame and punish parents, are directed towards bureaucratic functions such as ‘systems failure’, ‘quality control’, ‘institutional management’ and so on. To talk about literacy as an ‘output’ of schools may make perfect sense to those who accepted the 14 percent illiteracy rate as negligible in the first place, and divorced from the lives of real men and women. That perspective seems a bit unreal to persons who see literacy as being about cultivating the love of books and of reading. So where is the love – of self, of fellow Jamaicans, of reading – in this debate? I certainly haven’t seen or heard much lately.

The scarcity of love is evident in the deep-seated anti-literate sensibility in contemporary Jamaican society. This was not always so, of course. But at the moment, we need to confront how we consistently work against the very “outputs” we say are most desirable, and be willing to change.

The children I worked with were incredibly enthusiastic about the books they read and took home with them. And yet most of them were unable to read unassisted regardless of their age, precisely because they have very little contact with books. How does that happen? I probably first witnessed the effects of this sensibility when I was a teenager in Granville, St. James. The library branch located in my community was closed rather suddenly in the early-1980s. What was an oasis for many was immediately replaced by a grocery store. Years later, I learned that the Jamaica Public Library was asked to vacate the property; why they didn’t build or find another facility has never been answered. Ironically, the closing occurred just as the community’s population started to swell, eventually doubling in size from when I lived there.

To date, no equivalent public facilities have replaced the library; the only public space is the street. The working population lives amidst high unemployment, gun-related violence, poverty and all kinds of hustling characterize the life of people of all age groups there. Not a book in sight. At least two generations have now grown up there not knowing that there was ever a library nearby, some never even having visited the one in downtown Montego Bay. I’m sure other communities have suffered the same fate. Several of the vendor-parents from the Jones Town area noted that the mobile library unit had not shown up for months now. And that seems to be just fine with our politicians, policymakers, and business leaders. You can’t miss what you really never had – is that the logic? Love made scarce over and over again.

That anti-literate sensibility shows up in our libraries, which feel more like mausoleums complete with silent attendants – perceptibly bored librarians sending text messages, reading the newspaper and their Bibles, and who seem discomfited by a genuine question about the holdings. It is in the dress code set by the libraries, which requires that a potential patron – especially if one is a girl or woman –don the appropriate outfit prior to entering the building. A spontaneous trip to the library could quickly become very complicated. Apparently, access to reading material must be planned and carefully monitored. But even some plans do go awry; several vendors noted that the mobile library unit that covers Jones Town has not show up for several months! Love has been shelved for a future date.

Our bookstores are also complicit. For one thing, they often feel like extensions of the school. This is not hard to miss. Once you enter them, you can’t help but associate reading with school on account that one is far more likely to find textbooks and materials oriented towards classroom learning than any other kind of reading material. Forget that school is often a rather unpleasant place for many children, and where reading has nothing to do with pleasure.

Thanks to bookstores and schools, reading material exists in two discreet categories in the public consciousness: “textbooks” and “reading books”, respectively. I gave away many books, and the same question came at me repeatedly, from parent, children and onlookers alike: “Is that a reading book?” “No,” I said, “it is simply a book for you to enjoy, discover something new. All books are for reading.” For some reason, saying this felt heretical. They had definitely gotten the message though: Books are tools for formal education, rather than an entrée to new worlds, experiences and ideas. Access requires a booklist, an authority figure, directions, and a test. Enjoying what you read or even the act of reading is entirely secondary.

Ask a teacher when last they read a book for pleasure and shared that experience with their students. Indeed, ask a teacher when last they read a book, period. Chances are, reading in school is onerous, boring, full of corrections and anxiety, as students memorize words for the spelling test and barely get a chance to say what they think. That students actively smuggle and exchange ‘contraband’ like Harlequin, Mills & Boons and True Lives romance novels in schools and under threat of detention tells you what they will endure for the sake of reading something interesting. It takes love to transform these experiences into something affirming.

This instrumentalist approach to reading is reinforced at home as well: interacting with books is often treated as a secondary to far more important duties like agreeing with popular opinion, running errands, doing chores, or making room for other household members to watch the latest TV show. Books are often treated as something private to be protected, preferably by minimizing use of them. “Putting it up” is how I hear working-class people talk about books at home; locked away out of the sight and reach of everyone, to be admired or referenced occasionally, but without a designated place in the everyday life of a household. Books are a reward if she is not giving trouble, a way to keep him out of trouble. But they must always be returned to their place, out of sight. Books take up precious space, it seems, and thus are kept under the bed, tucked away in a drawer in the wardrobe, locked behind the doors of the bottom compartment of the whatnot.

So, if reading only goes with school, what goes with work and the rest of one’s life?

Thankfully, at least one [non-religious] bookstore now exists that promotes reading rather than schooling. The typewriter man who sells used books of all kinds on Barry Street in downtown Kingston is also on to something. We need more of each.

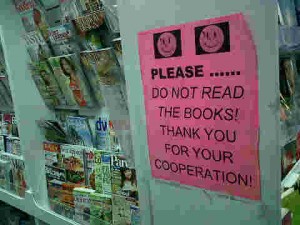

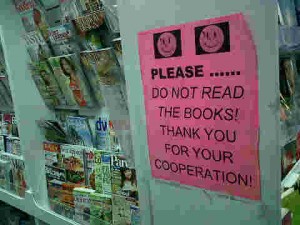

Some booksellers are quite daring in their anti-literate stance. You can’t miss it: the sign conspicuously located in the periodicals and fiction section of the bookstores and pharmacies that says “Do Not Read” in bold black letters.

"Do Not Read" sign often seen in supermarkets, pharmacies and bookstores in Jamaica (photo by Ingrid Riley)

The meaning is clear: buy or leave. I used to remove the signs; I no longer patronize places that have these signs. If I can’t read, I won’t buy. The logic employed by these booksellers openly contradicts the personal and intellectual freedom that comes from reading. They also reinforce the notion that only those who can afford to purchase the books, should be allowed to interact with them in a loving, even pleasurable way. Reading is pleasure. A significant majority of the Jamaican population lives by its wits and hands, and exchanges its labor for wages. Those persons not only guard, but also clean and maintain the spaces where books are sold, and where readings, book launches and literary events take place. Surely they too would enjoy reading or listening to a good story on the way to, from, or even during, work without having to budget for it?

That there is only one national literacy organization certainly helps to fuel this resistance to literacy. When Jamaica Movement for the Advancement of Literacy (JAMAL) became Jamaica Foundation for Lifelong Learning (JFLL) in 2006, the organization’s core identity – adult literacy – was subsumed under a rather nebulous textbook-sounding concept of “lifelong learning”. I don’t know if the term “literacy” bore a stigma that prevented the organization from doing its work. I do know that it can’t be helpful to refer to literacy education as something other than what it is, or to frame the costs of illiteracy purely in economic (and instrumental) terms.

The absence of dozens of NGO’s springing up to fill in the significant gaps not covered by JFLL is also indicative of our ambivalence about literacy. Instead, community-based initiatives that promote literacy are mostly spearheaded by non-Jamaicans and Jamaicans abroad. They come and go as they struggle to remain open. Acquiring the ability to read, write and reason is not so easy after all. One is not guaranteed to develop these abilities as a child in school, and it is even more effort to acquire them as an adult. Neither love nor literacy is available just so, it seems.

Our political culture is a hotbed of anti-literacy. For example, politicians gladly tell voters that the only book they read (and love!) is the Bible. Not surprisingly, they are more likely to offer personal opinions buttressed by oft-memorized scripture quotes over citing actual scholarship, research and policy reports in any given debate. There are still no organizations that do voter education or distribute basic information so that people can vote intelligently. Forget getting a diversity of perspectives on any issue through the existing print media. It’s not exactly fair to blame people for voting against their interests when nobody bothers to use basic tools – a flyer, a brochure, a periodical – to provide knowledge that can counter that ignorance.

At its most dangerous, anti-literacy tendencies are at the foundation for excluding or withholding materials – and thus knowledge – from public consumption. Recent objections to the translation of Bible into Patwa included the argument that it would be both pointless and unacceptable to allow Jamaicans to be able to read the language that most people speak, since writing it down would further legitimize its status as a language. Even the Ministry of Education takes on this censoring role, by monitoring what points of view and subject matter students are exposed to, and withdrawing information that is not perceived as worth knowing. Our students have little chance of experiencing the love of reading through entering unfamiliar worlds or experiences not already endorsed by adults in positions of authority.

These anti-literacy tendencies make it rare – and thus surprising – to see people reading at all. Waiting rooms/busloads/sidewalks full, and yet not a book, newspaper, pamphlet, or leaflet in sight. Yes, the occasional reader does show up: women with novels and the Bible; men with [often dated] newspapers and betting sheets, but they are far outnumbered by the non-readers around them. And not all of those non-readers want to remain that way. When I handed out several hundred sheets containing word search puzzles to adults in and around downtown areas, people constantly wanted more than the three sheets per person I had initially budgeted. “That’s all? I need a whole book of these!” said one man. “A person needs to keep their brain active,” another man said. “I like this; I can learn some new words,” said another. “This is a nice thing you are doing,” she said. “Come back again, yuh hear?”

All it takes to erase this anti-literate sensibility is persistence, imagination and a lot of love. Leave the tunnel vision behind and just think for a moment.

What would it mean for our many athletes to champion reading and to become literacy spokespersons themselves?

For one-tenth of all the monies spent by telecommunications companies to promote the latest technological gimmicks to be directed towards a multi-year national literacy campaign that aims to put a book in the hands of every newborn child and for every subsequent birthday until that child graduates from high school?

For high school principals to be paired with their primary school counterpart to build tutoring relationships between the schools?

For the libraries to develop year-round reading programs and competitions, promote family literacy, and devise ways for children to interact with writers, artists and illustrators?

For students to be encouraged to make and write books of their own, as well as to publish, compete and distribute them among their peers?

For NGOs to emerge whose sole focus is on nurturing a reading public?

For art galleries to develop public programs along with their exhibitions, which encourage children to read, write and think bout art?

For churches to offer to host family learning centers in every community?

For private sector companies to sponsor reading programs that are staffed by employees who volunteer?

For every politician to regularly visit the classrooms in order to read to the children, and to give priority to creating libraries and reading rooms in their constituencies?

For each of us to spend one hour per week reading with one child or adult?

That’s not all we could do, but doing those things would mean that we decided to show some love – of our fellow citizens, of ourselves and of the written word. Finally.