Originally submitted to Western Mirror, June 2015

Come the end of June, thousands of Jamaican children will exit the school gates, return home, pack away their school paraphernalia and begin the much-anticipated Summer Holiday. For the months of July and August, most will probably do a combination of the following: sit or lay around in boredom, watch lots of television, travel, visit relatives, play with friends, watch more television. Few will pick up and read a book during that entire time. And by book, I don’t mean schoolbooks i.e. the textbooks left over from the previous academic year that parents purchased to fulfill the requirements established by a particular school. Many children will turn to these, either by force or to alleviate boredom during unending summer days.

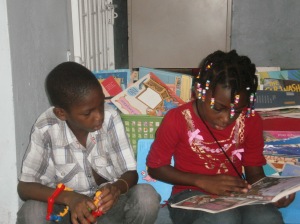

I mean books that children pick up to read for enjoyment. Books that they choose to read, not because there’s nothing else to read, but because they want to read that book. Books written to hook children into reading. Books that cause children to make elaborate plans to acquire, trade, hoard and share with their favorite persons. Books that are detached from tests and competitions. Books for which the only reward comes from having jumped into the book to experience the delight of wading around and feeling the story as it is told, and re-emerging thirsty, breathless, bragging, wanting more. Those books.

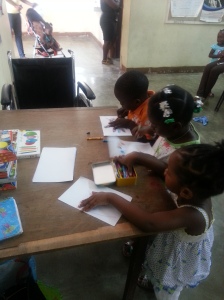

It is during the summer months where many children recover from the scholastic approach to books that they have endured over the academic year. They get to re-discover the pleasures and creativity involved with reading. Free from the strictures of homework and study regimen, children are able to browse, skim, read and re-read books that make them think, wonder, put themselves in someone else’s position, and activate their sense of curiosity. The more ideas and perspectives they are exposed to, the more connections they can make to the world around them, and the better they are able to question and sort out what they think about the ideas they encounter. Allowing children to choose what they read during the Summer holidays, and to read as much as they can, is good family and community practice.

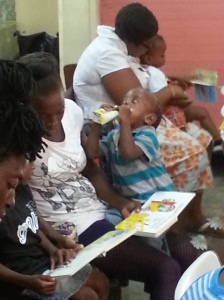

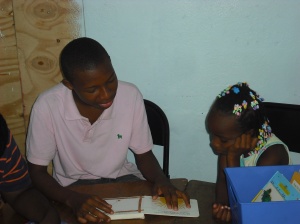

For children who are not fluent or confident readers, Summer is the ideal time for them to become immersed in the worlds that books offer to them without worrying about their literacy skills. Chances are, children who have difficulty reading the textbooks won’t want to read anything else. Reading is frustrating for them. And yet, it’s the other books – the non-school ones – that they are most likely to enjoy, and from which they will derive sufficient confidence and practice, without pressure or shame. No matter what they are reading, they will be practicing what they already know, learning new words and integrating ideas that they encounter. Most important is for adults to read aloud to children. Reading aloud is a critical way of providing support and encouragement that the children need; doing so also offers a stress-free experience for children to become more familiar with language and hear the words that they will eventually read on their own. Adults can also become better readers by doing so.

For children who are not fluent or confident readers, Summer is the ideal time for them to become immersed in the worlds that books offer to them without worrying about their literacy skills. Chances are, children who have difficulty reading the textbooks won’t want to read anything else. Reading is frustrating for them. And yet, it’s the other books – the non-school ones – that they are most likely to enjoy, and from which they will derive sufficient confidence and practice, without pressure or shame. No matter what they are reading, they will be practicing what they already know, learning new words and integrating ideas that they encounter. Most important is for adults to read aloud to children. Reading aloud is a critical way of providing support and encouragement that the children need; doing so also offers a stress-free experience for children to become more familiar with language and hear the words that they will eventually read on their own. Adults can also become better readers by doing so.

So then, why are there so few resources to support Jamaican children’s access to reading material during the summer months? One answer to that question can be found in the way that reading and books are perceived as expensive tools, a form of privilege, a means to an end, and deeply connected to school-based performance.

But the bigger problem lies in the fact that public policy does not treat access to education as a year-round issue. In truth, the laser-like focus on investment in schools and training institutions, while important to the broader education project, has come at a cost to children. That is, Jamaican policymakers continue to take a lopsided approach to education which makes it unlikely that most schoolchildren go home to communities where there are books waiting for them to dive into. In the current approach, communities and families are sidelined rather than treated as equally important partners in the work of education. Jamaican children deserve better.

The cost of ignoring community-level needs for education is most apparent during the summer months. Recall that the work of education is primarily relegated to schools and teachers, and funded as such. When schools are closed in the summer and teachers are on break, there are few options for childcare, reduced options for finding meals, let alone educational needs. Many parents, especially those who are employed, are at a loss for what to do with their children. Invariably, children are left unsupervised at home for long stretches of time, thus creating the conditions for a whole new set of problems to emerge. When families and communities are left on their own to figure out individually how and whether to provide learning opportunities for their children, social inequality wins. Those families that have the material means to enhance children’s learning are able to confer a “home advantage” that is reflected in children’s academic achievement later on. Indeed, it’s not a stretch to say that the paucity of state-supported afterschool programs and community-based initiatives in working-class communities can undermine the changes that are desired inside the schools! The current approach to education is neither just nor sustainable.

What would make a difference in children’s access to books and reading material during the summer months, as well as year-round? Greater public investment in the myriad other institutions that working-class and impoverished families interact with – healthcare, legal system, transit, housing, religion, community government – to make sure that they support and encourage children’s educational needs.

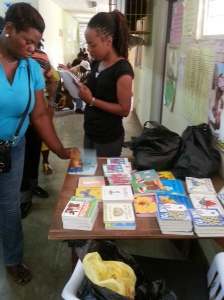

Improving access to books is a low-stakes way of creating learning opportunities for children growing up in impoverished and working-class environments.

Another way to address the problem of access is to amp up the visibility of public libraries and deepen their engagement with communities. Currently, publicly funded libraries are not as accessible as they need to be, even with the existence of a mobile library service. Social and economic inequality is carved into the landscape, and still makes a difference in which, how and whether children have the chance to enter the physical building or vehicle to take a book off the shelf. Too often, libraries in Jamaica are treated as extensions of schools, a place where the bright, studious children go to enhance their education and social skills. The children who need the support and resources available through that institution are probably not going to enter that space on their own. They need help to get there. Better outreach and support are needed for the young people who are struggling with reading.

Unfortunately, the public libraries in Jamaica can also be exclusionary rather than inviting spaces, limiting access to the very citizens who they might otherwise want to engage. One of the purposes of a public library is to entice and encourage children to step into the world of books, and to help them develop a long-term relationship with reading. What children or adults wear to the library is irrelevant to how and whether they will engage with the book. Indeed, attaching books and reading to respectability is exactly what the library should not do, not if it wants to pull in as many parents and families as possible. Everyone, including children, should feel like they belong and are welcome to the library, no matter what their situation. Whether they eventually migrate to electronic books or stick with the physical paper version, or go back and forth, children need access to the worlds of ideas and knowledge in them right now. Finding ways to expand access to the library will do a world of good for everyone.

Adults also need to read more. Children learn from adults about how to value and relate to books. The idea that reading a book is relevant only for school has become rooted over many generations. Inevitably then, some pare nts are just as likely as children to want to avoid books over the Summer holidays. The logic goes like this: books equal studying; ummer is not for studying, Summer is for rest and fun. Ergo, Summer is not for books. Except, that’s exactly the logic that also turns children off reading for pleasure and discourages healthy intellectual development. When adults present reading as taxing on the brain, as a means to a specific end, and only relevant to those who are in school, they introduce and reinforce anxieties that stifle children’s interest in reading. I can’t imagine that such attitudes are helpful to children, whether in the short and long-term. Certainly, many adults do need to evaluate how they talk about and relate to books, especially around children. But changing mindsets also requires a shift in public policy that encourages citizens to move beyond an instrumental approach to books and reading. Such policy might encourage every public institution, including the public libraries, to find ways to promote reading and literacy among families.

nts are just as likely as children to want to avoid books over the Summer holidays. The logic goes like this: books equal studying; ummer is not for studying, Summer is for rest and fun. Ergo, Summer is not for books. Except, that’s exactly the logic that also turns children off reading for pleasure and discourages healthy intellectual development. When adults present reading as taxing on the brain, as a means to a specific end, and only relevant to those who are in school, they introduce and reinforce anxieties that stifle children’s interest in reading. I can’t imagine that such attitudes are helpful to children, whether in the short and long-term. Certainly, many adults do need to evaluate how they talk about and relate to books, especially around children. But changing mindsets also requires a shift in public policy that encourages citizens to move beyond an instrumental approach to books and reading. Such policy might encourage every public institution, including the public libraries, to find ways to promote reading and literacy among families.

Finding creative ways to strengthen the system of distribution of books to and for children will make a tremendous difference in the lives of Jamaican children, families and communities. Doing so will require taking a much broader approach to education than currently obtains. It means spreading out the work and  getting more people to become invested in educating and advocating for children’s needs. Whether that means teachers working with bookstores to encourage summer reading, or churches get retired teachers to organize reading programs for new parents, or sports clubs do fundraisers to create a bookshelf in every shop in their community, or service clubs do book drives to support the school libraries in the community, or teachers are hired by community centers to develop educational programs, there is no limit to what ordinary citizens can do to invest in the wellbeing of all children and families. Making books available to children in working-class and impoverished communities during the Summer holidays is one small way to signal that investment. It is simply the just thing to do.

getting more people to become invested in educating and advocating for children’s needs. Whether that means teachers working with bookstores to encourage summer reading, or churches get retired teachers to organize reading programs for new parents, or sports clubs do fundraisers to create a bookshelf in every shop in their community, or service clubs do book drives to support the school libraries in the community, or teachers are hired by community centers to develop educational programs, there is no limit to what ordinary citizens can do to invest in the wellbeing of all children and families. Making books available to children in working-class and impoverished communities during the Summer holidays is one small way to signal that investment. It is simply the just thing to do.

All images courtesy of Granville Reading & Art Programme, 2012-2014. Do not copy or post images elsewhere without permission.