A Love Letter to Jamaican Girls

January 5, 2017

I.

I have been thinking about love letters lately. Do you remember the ones you used to write or receive when you were a teenager? You would write it in secret, always when you were bored or supposed to be doing something else, and would hide it until you had a chance to give it to the intended recipient.

The prose was flowery, full of rhymes, clichés of all sorts filled the pages, lots of hearts and roses and declarations of undying affection and adoration for every aspect of the person. The receiver would hide it in a special place, to read by themselves, over and over again.

With scraps of paper, borrowed pens and makeshift envelopes, we felt it important to record those feelings, to release them from captivity and hope that the person who received it would know what feelings they had inspired.

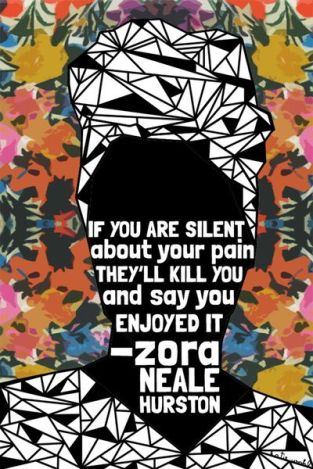

Jamaican girls need a different kind of love letter right now. Not the ones with the hearts and flowers, or written for humor’s sake, but the ones that will affirm and build them up against the ugly, hateful, toxic and deeply unloving ideas being spread about them.

Letters that anoint girls with the same intention and care as if she had journeyed to a balmyard for a bath.

Letters that girls can carry in their bosoms and pockets as spiritual defense, in the tradition of our grandmothers who used to carry herbs wrapped in pieces of cloth and tied to their brassieres to ward off evil.

Letters that make them feel strong, powerful and untouchable, as if they walk among us, but are not of us.

Letters that heal, that empower them to resist, that encourage girls to see each other as her sister’s keeper, to see herself in other girls, and to protect her fiercely.

II.

It is truly frightening how much Jamaican society has become invested in telling girls exactly how little they are valued as persons. Maybe this isn’t new though; something I hope to investigate more over this year. But it’s really not an exaggeration to say that nearly everything that is being said to and about Jamaican girls in public – on social media, in the taxis, comments from random strangers, sermons from the pulpit – is anything but loving.

The favourite response is to blame girls when they are violated by men. Sadly, even girls themselves participate to prove that they are “better”.

Right after her body is found dismembered in a gully, canefield or latrine, or the unspeakable violence against her has been made public, the unofficial campaign to re-victimize her unfolds:

What could she have done to cause this to happen?

Why was she on that road?

What was she doing with him?

She must have wanted it or she wouldn’t have gone there.

She acts too grown for her age.

She should have said something.

She or her mother is being paid so nobody should complain.

She wants too much attention.

If you listen carefully, you can hear it: the deep dislike and distrust of girls. They are bad until they prove otherwise. In the most casual conversation among Jamaicans, it takes nothing for adults to start accusing girls of being “too much” – too fast, acting too grown-up, too curious, too impatient, too impetuous, too loud, too mouthy – too whatever we don’t like or value in someone else. In the stories that we like to tell, girls are, by definition, temptresses, schemers, always wanting to lure men into compromising positions.

The intention, whether stated or not, is always to blame girls for the harm that comes to them, and to remind us that men’s “nature” is particularly susceptible to being unleashed by prepubescent girls. Whether it is a group of boys in a bathroom or a 62 year old man who is reputed to be a molester of an entire family of girls, men are presumed to be powerless to resist her.

And of course, the time-honoured ammunition for this position: the Bible. There is simply no shortage of favourite misinterpretations to be launched from pulpits, verandahs and Facebook posts to defend sexual violence against girls.

Young women are also harmed by the onslaught of negative talk. Just listen to the words adults use to curse them, to make them feel ugly, small, worthless, powerless, like nothing. Instead of teaching girls how to love themselves and develop a positive self-identity, adults are quick to find ways to control and beat them into submission: ugly uniforms, limits on their physical movement, shaming them, denying them information, feeding them with outdated and unproven ideas, imposing silence, physically beating them. In the warped way of many adults, this formula of “bending”, “breaking” and “moulding” is what will produce meek and mild girls, girls who do what they are told and march in exactly the ways they have been directed by adults, especially men.

Young women are also harmed by the onslaught of negative talk. Just listen to the words adults use to curse them, to make them feel ugly, small, worthless, powerless, like nothing. Instead of teaching girls how to love themselves and develop a positive self-identity, adults are quick to find ways to control and beat them into submission: ugly uniforms, limits on their physical movement, shaming them, denying them information, feeding them with outdated and unproven ideas, imposing silence, physically beating them. In the warped way of many adults, this formula of “bending”, “breaking” and “moulding” is what will produce meek and mild girls, girls who do what they are told and march in exactly the ways they have been directed by adults, especially men.

The negative talk that is constantly hurled at girls seeps in, and slowly eats away at how girls see themselves and what they learn to expect in terms of how they should be treated. Too many girls spend their adolescent and adult years denying or burying their experiences of violence and humiliation, just biting their tongues and biding their time.

If they are lucky, they learn how to love themselves and the children that they are responsible for. But what is more likely is that their rage and buried hurt visits their children – through beatings, hurtful words, silence.

When adults deny girls love, we set them up for failure. We make it more likely for them to make poor choices in their personal lives because they are willing to go wherever they will find something that feels like love. When we choose to act surprised when girls demonstrate agency or act out their self-hatred, we are denying our responsibility in killing their dreams and slaughtering their self-concept.

III.

All of this is why Jamaican girls need love letters.

They need to be told that they are beautiful, smart, courageous, talented, that they matter, that they are poised to do great things, and that they hold the future in their hands.

They need to be told that being outspoken is a good thing, that bold girls become great women, that they don’t need permission to think. They need to be told that they are no better or worse than any other girl who is different from them. They need to be told that all girls deserve the same opportunities to shine.

What they need to hear is that it is not ok for anyone to hurt them. They need to be told that their bodies belong to them and them alone. They don’t have to keep any secret when men and boys do unspeakable things to them. And they don’t have to respect any man or do what he says just because of the political party he belongs to, which business he runs, whether he carries a gun or a bible. Our girls need to know that they are not required to respect authority when that means they have to suffer in silence.

We need to tell girls that they don’t have to be afraid. They need daily reminders that they already know how to be courageous. That surviving the journey from home to school to church to shop and back home with their dignity intact is an act of courage and defiance. They need to know that other women have walked this path too, have survived and are willing to stand up for them.

We have to tell girls that their dignity is theirs to own and defend, and that no one can take that from them. No girl is dispensable or worthless.

All girls, and especially those who come from under-resourced families and communities, need psychological armor to protect them from the public assault on their character, their persons and on their lives. When we surround them with love, they become invincible. They are counting on us as adults, and we need to stop disappointing them.

So, here’s to you, Jamaican Girl!

Even if:

- You live in the roughest part of the poorest community in your parish.

- You spend all daylight hours sitting under a tree or in somebody else’s place just to avoid your own home or your classroom

- The pastor/deacon/church brother has taken a liking to “laying on hands” during every prayer meeting

- You were told that you are black and ugly like sin and you believe it

- You are the “pet” and favorite toy of your cousin/uncle/stepfather/father/grandfather/neighbor and you don’t know why

- You believe that you are better than other girls because you are sure that what happens to them could never happen to you

- You have to decide between skipping school and asking the taxi-driver to drop you in exchange for a feel-up and some credit

- You do not attend a “prominent” school, your picture is not in the newspaper, and you did not pass 10 subjects

- You believe that it is a compliment when men of all ages call to you on the street

- You have been held down, felt up, battered and bruised over and over again because they say that you are not a virgin so it doesn’t matter

- Your family thinks you are worthless because you were raped

- You have been told that you need to start fending for yourself, including having sex with older men, in order to pay for light bill and lunch money.

- Your teachers tell you that good money is being wasted to send you to school

- You can barely read or write and don’t speak any English

- You bleach your skin because you believe that you will be more attractive and men will pay more attention to you and help you get ahead

- Your community is a place where girls like yourself feels trapped or fantasizes about escaping from.

Regardless of where you live, what your situation, how well you speak English:

You are precious.

You are loved.

You matter.

You are a fighter, you are capable of great things.

We believe you.

We believe in you.

We have not always spoken up in your defence when we should have, but we see you.

We know that there’s no future if you don’t make it. There are many, many of us who are fighting for you and for your survival.

Stay strong, Jamaican Girl!

I love you.

Create your own love letter!